Mayan Society

National Geographic - December 7, 2006

The Mayan civilization was not one unified empire, but rather a multitude of separate entities with a common cultural background. Similar to the Greeks, they were religiously and artistically a nation, but politically sovereign states.

As many as twenty such states existed on the Yucatan Peninsula, but although a woman has, on rare occasions, ascended to the ruling position, she has never acquired the title of 'mah kina'.

The Mayans were the most important of the cultured native peoples of North America, both in the degree of their civilization and in population and resources, formerly occupying a territory of about 60,000 square miles, including the whole of the peninsula of Yucatan, Southern Mexico, together with the adjacent portion of Northern Guatemala, and still constituting the principal population of the same region outside of the larger cities.

The most important tribes or nations, after the Maya proper, were the Quiche and Cakchiquel of Guatemala. All the tribes of this stock were of high culture, the Mayan civilization being the most advanced and probably the most ancient, in aboriginal North America. They still number altogether about two million souls.

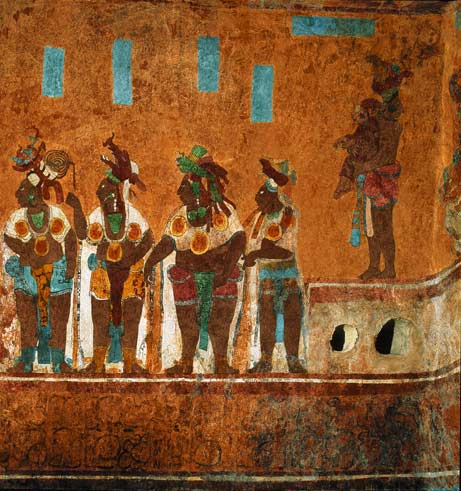

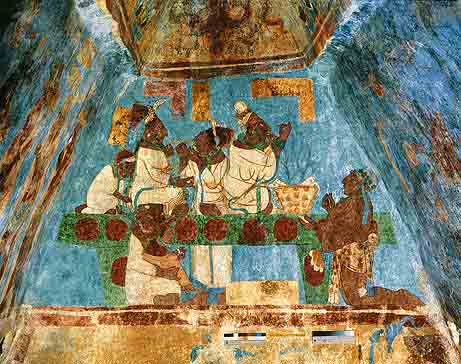

There was a distinct class system in ancient Maya times. Between the ruling class and the farmer/laborer, there must have been an educated nobility who were scribes, artists and architects. Evidence of their skill and innovation remains in works of stone, stucco, jade, bone, pottery, obsidian and flint. There is no evidence of a priesthood and it is likely that priestly duties were performed by the ruler.

The ordinary garment of men was a cotton breechcloth wrapped around the middle, with sometimes a sleeveless shirt, either white or dyed in colors.

The women wore a skirt belted at the waist, and plaited their hair in long tresses. Sandals were worn by both sexes. Tattooing and head-flattening were occasionally practised, and the face and body were always painted. The Maya, then as now, were noted for personal neatness and frequent use of both cold and hot baths.

Culturally the area is divided into three sections: the northern, central and southern regions. The earliest evidence of the Maya civilization is found in the southern region. At Izapa carvings depict gods that were the precursors of the Classic deities and at Kaminaljuyu glyphs on stelea foreshadow the Maya writing system. The area was clearly influenced by the Olmec.

The central region includes the southern lowlands, from Tabasco in the Northwest to Belize and Guatemala's Motagua River region in the southeast. Here is where the Classic Maya flourished, along the Usumacinta River and throughout the Peten.

The northern region, which encompasses the northern lowlands, was populated by the Maya in the Late Classic period, when influence from central Mexico created a hybrid Maya/Toltec culture, and was home to the Maya well into the Post-Classic period.

Under the ancient system, the Maya Government was an hereditary absolute monarchy, with a close union of the spiritual and temporal elements, the hereditary high priest, who was also king of the sacred city of Izamal, being consulted by the monarch on all important matters, besides having the care of ritual and ceremonials.

On public occasions the king appeared dressed in flowing white robes, decorated with gold and precious stones, wearing on his head a golden circlet decorated with the beautiful quetzal plumes reserved for royalty, and borne upon a canopied palanquin.

The provincial governors were nobles of the four royal families, and were supreme within their own governments.

The rulers of towns and villages formed a lower order of nobility, not of royal blood. The king usually acted on the advice of a council of lords and priests.

The lords alone were military commanders, and each lord and inferior official had for his support the produce of a certain portion of land which was cultivated in common by the people.

They received no salary, and each was responsible for the maintenance of the poor and helpless of his district. The lower priesthood was not hereditary, but was appointed through the high priest. There was also a female priesthood, or vestal order, whose head was a princess of royal blood.

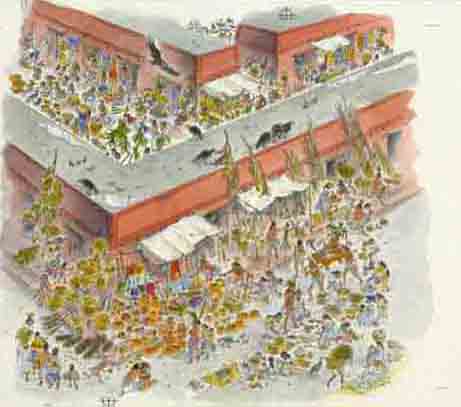

The plebeians were farmers, artisans, or merchants; they paid taxes and military service, and each had his interest in the common land as well as his individual portion, which descended in the family and could not be alienated.

Slaves also existed, the slaves being chiefly prisoners of war and their children, the latter of whom could become freemen by putting a new piece of unoccupied ground under cultivation.

Society was organized upon the clan system, with descent in the male line, the chiefs being rather custodians for the tribe than owners, and having no power to alienate the tribal lands. Game, fish, and the salt marshes were free to all, with a certain portion to the lords.

Taxes were paid in kind through authorized collectors. On the death of the owner, the property was divided equally among his nearest male heirs.

The more important cases were tried by a royal council presided over by the king, and lesser cases by the provincial rulers or local judges, according to their importance, usually with the assistance of a council and with an advocate for the defense.

Crimes were punished with death - frequently by throwing over a precipice - enslavement, fines, or rarely, by imprisonment.

The code was merciful, and even murder could sometimes be compounded by a fine.

Children were subject to parents until of an age to marry, which for boys was about twenty.

The children of the common people were trained only in the occupation of their parents, but those of the nobility were highly educated, under the care of the priests, in writing, music, history, war, and religion.

The daughters of nobles were strictly secluded, and the older boys in each village lived and slept apart in a public building. Birthdays and other anniversaries were the occasions of family feasts.

Marriage between persons of the same gender was forbidden, and those who violated this law were regarded as outcasts.

Marriage within certain other degrees of relationship - as with the sister of a deceased wife, or with a mother's sister - was also prohibited.

Polygamy was unknown, but concubinage was permitted, and divorce was easy. Marriages were performed by the priests, with much ceremonial rejoicing, and preceded by a solemn confession and a baptismal rite, known as the "rebirth", without which there could be no marriage.

No one could marry out of his own rank or without the consent of the chief of the district.

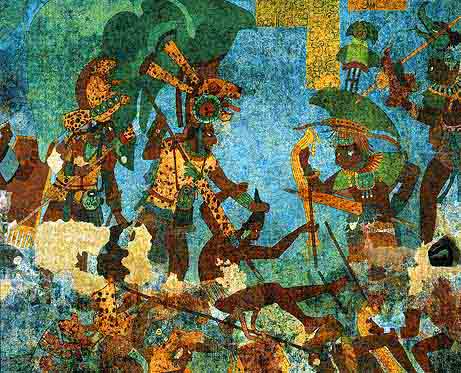

The Mayans were expert and determined warriors, using the bow and arrow, the dart with throwing-stick, the wooden sword edged with flints, the lance, sling, copper axe, shield of reeds, and protective armour of heavy quilted cotton.

They understood military tactics and signalling with drum and whistle, and knew how to build barricades and dig trenches. Noble prisoners were usually sacrificed to the gods, while those of ordinary rank became slaves.

Their object in war was rather to make prisoners than to kill.

As the peninsula had no mines, the Maya were without iron or any metal excepting a few copper utensils and gold ornaments imported from other countries.

Their tools were almost entirely of flint or other stone, even for the most intricate monumental carving.

For household purposes they used clay pottery, dishes of shell, or gourds. Their pottery was of notable excellence, as were also their weaving, dyeing, and feather work.

Along the coast they had wooden dugout canoes capable of holding fifty persons.