Tattooing is one of the oldest art forms on the planet, dating to prehistoric times and cave dwellers who often created tattooes as part of ritual practices linked to shamanism, protection, connection with their gods, and embuing them with magica powers. Early tattooing was used to symbolize the fertility of the earth and of womankind, preservation of life after death, the sacredness of chieftainship and other cultural factors.

Tattooed markings on skin and incised markings in clay provide some of the earliest evidence that humans have long practiced a wide range of body art. The written accounts of early European explorers also attest to the elaborate and widespread nature of tattooing in various parts of the world, providing an insight into traditions that had their origins deep in the past.

Marriage tattoos have been particularly popular to insure that you can find your lawful spouse or spouses in the afterlife, even if you have passed 'through the veil,' many years apart. Ancient Ainu marriage rites state that a woman who marries without first being tattooed, in the proper manner, commits a great sin and when she dies; she will go straight to God.

Tattooing as a rite of adulthood, or passage into puberty, was another common tattoo ritual. If a girl can't take the pain of tattooing, she is un-marriageable, because she will never be able to deal with the pain of child birth. If a boy cannot deal with the pain of his puberty tattoos, he is considered to be a bad risk as a warrior, and could become an outcast.

Since the dawn of tattooing, people have been marking themselves with the signs of their totem animals. On the outer level of meaning, they are trying to gain the strengths and abilities of the totem animal. On a more inner and mystical level, totem animals mean that the bearer has a close and mysterious relationship with this animal spirit as his guardian. Totem animal tattoos often double as clan or group markings. Modern dragon, tiger, and eagle tattoos often subconsciously fall into this category. My snake tattoos are examples of DNA and the human biogenetic experiment.

Another common practice was tattooing for health wherein the tattooing of a god was placed on the afflicted person, to fight the illness for them. An offshoot of tattooing for health is tattooing to preserve youth. Maori girls tattooed their lips and chin, for this reason. When an old Ainu lady's eyesight is failing, she can re-tattoo her mouth and hands, for better vision. This is still practiced today.

Tattoos for general good luck are found world-wide. A man in Burma who desires good luck will tattoo a parrot on his shoulder. In Thailand, a scroll representing Buddha in an attitude of meditation is considered a charm for good luck. In this charm, a right handed scroll is masculine and a left handed scroll is feminine. Today, in the West, you can see dice, spades, and Lady Luck tattoos, which are worn to bring luck.

History

Prehistoric Times

Archaeologists find 2,500-year-old mummy in Mongolia, tattoos, blond hair and a felt hat

PhysOrg - August 25, 2006

Tattooing has been a Eurasian practice since Neolithic times."Otzi the Iceman",dated circa 3300 BC, exhibits possible therapeutic tattoos (small parallel dashes along lumbar and on the legs). Tarim Basin (West China, Xinjiang) revealed several tattooed mummies of a Western (Western Asian/European) physical type. Still relatively unknown (the only current publications in Western languages are those of J P. Mallory and V H. Mair, The Tarim Mummies, London, 2000), some of them could date from the end of the 2nd millennium BCE.

The world's most spectacular tattooed mummy was discovered by Russian anthropologist Sergei Ivanovich Rudenko in 1948 during the excavation of a group of Pazyryk tombs about 120 miles of the border between China and Russia.

These mummies were found in the High Altai Mountains of western and southern Siberia and date from around 2400 years ago. The tattoos on their bodies represent a variety of animals. The griffins and monsters are thought to have a magical significance but some elements are believed to be purely decorative. Altogether the tattoos are believed to reflect the status of the individual.

Three tattooed mummies (c. 300 BCE) were extracted from the permafrost of Altaï in the second half of the 20th century (the Man of Payzyrk, during the 1940s; one female mummy and one male in Ukok plateau, during the 1990s). Their tattooing involved animal designs carried out in a curvilinear style.

The Man of Pazyryk was also tattooed with dots that lined up along

the spinal column (lumbar region) and around the right ankle.

The Pazyryks were formidable iron age horsemen and warriors who inhabited the steppes of Eastern Europe and Western Asia from the sixth through the second centuries BC. They left no written records, but Pazyryk artifacts are distinguished by a sophisticated level of artistry and craftsmanship. The Pazyryk tombs discovered by Rudenko were in an almost perfect state of preservation. They contained skeletons and intact bodies of horses and embalmed humans, together with a wealth of artifacts including saddles, riding gear, a carriage, rugs, clothing, jewelry, musical instruments, amulets, tools, and, interestingly, hash pipes, described by Rudenko as "apparatus for inhaling hemp smoke".

Also found in the tombs were fabrics from Persia and China, which the Pazyryks must have obtained on journeys covering thousands of miles. Rudenko's most remarkable discovery was the body of a tattooed Pazyryk chief: a thick-set, powerfully built man who had died when he was about 50. Parts of the body had deteriorated, but much of the tattooing was still clearly visible. The chief was elaborately decorated with an interlocking series of designs representing a variety of fantastic beasts.

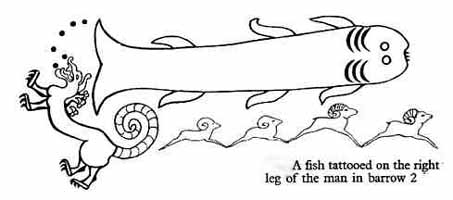

The best preserved tattoos were images of a donkey, a mountain ram, two highly stylized deer with long antlers and an imaginary carnivore on the right arm. Two monsters resembling griffins decorate the chest, and on the left arm are three partially obliterated images which seem to represent two deer and a mountain goat.

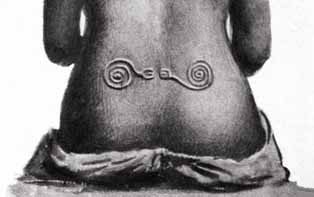

On the front of the right leg a fish extends from the foot to the knee. A monster crawls over the right foot, and on the inside of the shin is a series of four running rams which touch each other to form a single design. The left leg also bears tattoos, but these designs could not be clearly distinguished. In addition, the chief's back is tattooed with a series of small circles in line with the vertebral column. This tattooing was probably done for therapeutic reasons. Contemporary Siberian tribesmen still practice tattooing of this kind to relieve back pain.

No instruments specifically designed for tattooing were found, but the Pazyryks had extremely fine needles with which they did miniature embroidery, and these were undoubtedly used for tattooing In the summer of 1993 another tattooed Pazyryk mummy was discovered in Siberia's Umok plateau. It had been buried over 2,400 years ago in a casket fashioned from the hollowed-out trunk of a larch tree. On the outside of the casket were stylized images of deer and snow leopards carved in leather. Shortly after burial the grave had apparently been flooded by freezing rain and the entire contents of the burial chamber had remained frozen in permafrost.

The body was that of a young woman whose arms had been tattooed with designs representing mythical creatures like those on the previously discovered Pazyryk mummy. She was clad in a voluminous white silk dress, a long crimson woolen skirt and white felt stockings.

On her head was an elaborate headdress made of hair and felt - the first of its kind ever found intact. Also discovered in the burial chamber were gilded ornaments, dishes, a brush, a pot containing marijuana, and a hand mirror of polished metal on the wooden back of which was a carving of a deer. Six horses wearing elaborate harnesses had been sacrificed and lay on the logs which formed the roof of the burial chamber.

Considering the number of tattooed mummies which have been discovered, it is apparent that tattooing was widely practiced throughout the ancient world and was associated with a high level of artistic endeavor. The imagery of ancient tattooing is in many ways similar to that of modern tattooing.

All of the known Pazyryk tattoos are images of animals. Animals are the most frequent subject matter of tattooing in many cultures and are traditionally associated with magic, totemism, and the desire of the tattooed person to become identified with the spirit of the animal. Tattoos which have survived on mummies suggest that tattooing in prehistoric times had much in common with modern tattooing, and that tattooing the world over has profound and universal psychic origins.

Tattooing for spiritual and decorative purposes in Japan is thought to extend back to at least the Jomon or paleolithic period (approximately 10,000 BCE) and was widespread during various periods for both the Japanese and the native ainu Chinese visitors observed and remarked on the tattoos in Japan (300 BCE).

In Japanese the word used for traditional designs or those that are applied using traditional methods is irezumi ("insertion of ink"), while "tattoo" is used for non-Japanese designs. The earliest evidence of tattooing in Japan comes from figurines called dogu. Most of these date to 3000 years ago and display similar markings to the tattooed mouths found among the women of the Ainu (the Indigenous people of Japan).

Tattoo enthusiasts may refer to tattoos as tats, ink, art or work, and to tattooists as artists. The latter usage is gaining support, with mainstream art galleries holding exhibitions of tattoo designs and photographs of tattoos. Tattoo designs that are mass-produced and sold to tattoo artists and studios and displayed in shop are known as flash.

Tattooing has also been featured prominently in one of the Four Classic Novels in Chinese literature, Water Margin, in which at least three of the 108 characters, Lu Zhi Chen, Shi Jin, and Yan Chen are described as having tattoos covering nearly the whole of their bodies. In addition, Chinese legend has it that the mother of Yue Fei, the most famous general of the Song Dynasty, tattooed the words jin zhong bao guo on his back with her sewing needle before he left to join the army, reminding him to "repay his country with pure loyalty".

Egypt

These dot-and-dash patterns have been seen for many years throughout Egypt. This pattern and skill of tattoo may have been borrowed from the Nubians. The art of tattoo developed during the Middle Kingdom and flourished beyond. The evidence to date suggests that this art form was restricted to women only, and usually these women were associated with ritualistic practice. These mummies give us site into how long this art form has been practiced and how their art was displayed. From continent to continent this art form has developed and transformed. Through the Egyptian eyes to other cultures, tattoo is something that satisfies various needs and interest.

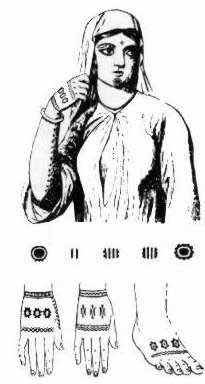

A second mummy also found depicted this same type of line pattern (the dancer). This mummy also had a cicatrix pattern over her lower pubic region. In the figure to the right you can see the various patterns as they are displayed on the body. The various design patterns also appeared on several figurines that date to the Middle Kingdom, these figurines have been labeled the "Brides of Death." The figurines are also associates with the goddess Hathor. All tattooed Egyptian mummies found to date are female. The location of the tattoos on the lower abdomen are thought to be linked to fertility.

Egyptian tattooing was someitmes related to the sensual, erotic, and emotional side of life, and all these themes are found in tattooing today.

Egypt 1800's

Middle East

An archaic practice in the Middle East involved people cutting themselves and rubbing in ash during a period of mourning after an individual had died. It was a sign of respect for the dead and a symbol of reverence and a sense of the profound loss for the newly departed; and it is surmised that the ash that was rubbed into the self-inflicted wounds came from the actual funeral pyres that were used to cremate bodies. In essence, people were literally carrying with them a reminder of the recently deceased in the form of tattoos created by ash being rubbed into shallow wounds cut or slashed into the body, usually the forearms.

Australia

Early Aussie Tattoos Match Rock Art Discovery - June 2, 2008

Body art was all the rage in early Australia, as it was in many other parts of the ancient world, and now a new study reports that elaborate and distinctive designs on the skin of indigenous Aussies repeated characters and motifs found on rock art and all sorts of portable objects, ranging from toys to pipes. The study not only illustrates the link between body art, such as tattoos and intentional scarring, with cultural identity, but it also suggests that study of this imagery may help to unravel mysteries about where certain groups traveled in the past, what their values and rituals were, and how they related to other cultures.

"Distinctive design conventions can be considered markers of social interaction so, in a way (they are) a cultural signature of sorts that archaeologists can use to understand ways people were interacting in the past," author Liam Brady of Monash University's Center for Australian Indigenous Studies, told Discovery News.

For the study, published in the latest issue of the journal Antiquity, Brady documented rock art drawings; images found on early turtle shell, stone and wood objects, such as bamboo tobacco pipes and drums; and images that were etched onto the human body through a process called scarification. "In a way, a scarred design could be interpreted as a tattoo," Brady said. "It was definitely a distinctive form of body ornamentation and it was permanent since the design was cut into the skin. Evidence for scarification is primarily via (19th century) anthropologists -- mainly A.C. Haddon -- who took black and white photographs of some designs, as well as drawing others into his notebooks in the late 1800's," he added.

Both Haddon and Brady focused their attention on a region called the Torres Strait. This is a collection of islands in tropical far northeastern Queensland. The islands lie between Australia and the Melanesian island of New Guinea. Although people were living in the Torres Strait as early as 9,000 years ago, when sea levels were lower and a land bridge connected Australia with New Guinea, archaeological exploration of the area only really began with Haddon's 19th century work. Since body art, rock art, wooden objects and other tangible items have a relatively short shelf life, Haddon's collections and data represent some of the earliest confirmed findings for the region.

Brady determined that within the body art, rock art and objects, four primary motifs often repeated: a fish headdress, a snake, a four-pointed star, and triangle variants. The fish headdress, usually made of a turtle shell decorated with feathers and rattles, was worn during ceremonies and has, in at least one instance, been linked to a "cult of the dead." The triangular designs, on the other hand, were often scarred onto women's skin and likely indicated these individuals were in mourning. Analysis of the materials found that two basic groups -- horticulturalists and hunter-gatherers -- inhabited the Torres Strait during its early history. Aboriginal people at Cape York, a peninsula close to Australia, had "a different artistic system in operation, which did not incorporate many designs from Papua New Guinea," Brady said.

Based on land locations where the body art and object imagery were found, as well as the nature of the designs, Brady concludes that the Cape York residents were the hunter-gatherers, while groups in more northerly locations within Torres Strait appear to have been horticulturalists. Since imagery mixed and matched more among the early farmers, Brady concludes they enjoyed kinship links, and engaged in extensive trade, with Papua New Guinea groups. In the future, similar studies could help to identify cultural groups in other regions, while also revealing their social interactions. Such studies could prove particularly useful for other parts of Australia and New Zealand, where tattooing and body art, as well as totems -- protection entities often depicted with colorful imagery -- were common.

Recently, for example, the Field Museum in Chicago returned the human remains of 14 Maori native New Zealanders back to their country of origin. The remains are now at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa. Included in the collection of mandibles, crania and other bones is "one preserved head with facial tattoos," according to a Field Museum announcement. In an act of repatriation, nine tattooed Maori heads were also recently gifted to Te Papa by Scotland's Aberdeen Museum. Te Taru White, a Maori specialist at Te Papa, said the "ancestors" made "the long journey home to New Zealand and to their people." The heads are now in a consecrated, sacred space within the New Zealand museum, where they may be studied and researched further. In Brady's case, his work was undertaken as part of collaborative research projects initiated by certain Torres Strait and Aboriginal communities.

The term "tattoo" is traced to the Tahitian tatu or tatau, meaning to mark or strike, the latter referring to traditional methods of applying the designs.

The earliest evidence of tattooing in the Pacific is in the form of this pottery shard which is approximately 3000 years old. The Lapita face shows dentate (pricked) markings on the nose, cheeks and forehead, suggestive of the technique of tattoo application.

pottery sherd was recently found on Boduna Island.

Painted Past: Borneo's Traditional Tattoos

National Geographic - June 18, 2004

Between 1766 and 1779, Captain James Cook made three voyages to the South Pacific, the last trip ending with Cook's death in Hawaii in February, 1779. When Cook and his men returned home to Europe from their voyages to Polynesia, they told tales of the 'tattooed savages' they had seen.

Cook's Science Officer and Expedition Botanist, Sir Joseph Banks, returned to England with a tattoo. Banks was a highly regarded member of the English aristocracy and had acquired his position with Cook by putting up what was at the time the princely sum of some ten thousand pounds in the expedition. In turn, Cook brought back with him a tattooed Tahitian chief, whom he presented to King George and the English Court. Many of Cook's men, ordinary seamen and sailors, came back with tattoos, a tradition that would soon become associated with men of the sea in the public's mind and the press of the day. In the process sailors and seamen re-introduced the practice of tattooing in Europe and it spread rapidly to seaports around the globe.

It was in Tahiti aboard the Endeavour, in July of 1769, that Cook first noted his observations about the indigenous body modification and is the first recorded use of the word tattoo. In the Ship's Log, Cook recorded this entry: "Both sexes paint their bodies, "Tattow," as it is called in their Language. This is done by inlaying the colour of black under their skins, in such a manner as to be indelible. This method of Tattowing is a painful operation, especially the Tattowing of their buttocks. It is performed but once in their lifetimes.

The British Royal Court must have been fascinated with the Tahitian chief's tattoos, because the future King George V had himself inked with the 'Cross of Jerusalem' when he traveled to the Middle East in 1892. He also received a dragon on the forearm from the needles of an acclaimed tattoo master during a visit to Japan. George's sons, The Duke of Clarence and The Duke of York were also tattooed in Japan while serving in the British Admiralty, solidifying what would become a family tradition.

Taking their sartorial lead from the British Court, where Edward VII followed George V's lead in getting tattooed; King Frederick IX of Denmark, the King of Romania, Kaiser Wilhelm II, King Alexander of Yugoslavia and even Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, all sported tattoos, many of them elaborate and ornate renditions of the Royal Coat of Arms or the Royal Family Crest. King Alfonso of modern Spain also had a tattoo.

Tattooing spread among the upper classes all over Europe in the nineteenth century, but particularly in Britain where it was estimated in Harmsworth Magazine in 1898 that as many as one in five members of the gentry were tattooed. There, it was not uncommon for members of the social elite to gather in the drawing rooms and libraries of the great country estate homes after dinner and partially disrobe in order to show off their tattoos. Aside from her consort Prince Albert, there are persistent rumours that Queen Victoria had a small tattoo in an undisclosed 'intimate' location; Denmark's king Frederick was filmed showing his tattoos taken as a young sailor. Winston Churchill's mother, Lady Randolph Churchill, not only had a tattoo of a snake around her wrist, which she covered when the need arose with a specially crafted diamond bracelet, but had her nipples pierced as well. Carrying on the family tradition, Winston Churchill was himself tattooed. In most western countries tattooing remains a subculture identifier, and is usually performed on less-often exposed parts of the body.

Pre-Christian caltic and other central and northern European tribes were often heavily tattooed, according to surviving accounts. The pictures were famously tattooed (or scarified) with elaborate dark blue woad (or possibly copper for the blue tone) designs. Julius Caesar described these tattoos in Book V of his Gallic Wars (54 BCE).

Ahmad ibn Fadlan also wrote of his encounter with the Scandinavian Rus' tribe in the early 10th century, describing them as tattooed from "fingernails to neck" with dark blue "tree patterns" and other "figures."

During the gradual process of Christianization in Europe, tattoos were often considered remaining elements of paganism and generally legally prohibited. According to Robert Graves in his book The Greek Myths tattooing was common amongst certain religious groups in the ancient Mediterranean world, which may have contributed to the prohibition of tattooing in Leviticus.

The Greek learned tattooing from the Persians. Tattooing is mentioned in accounts by Plato, Aristophanes, Julius Caesar and Herodotus. Tattoos were generally used to mark slaves and punish criminals.

The Romans tattooing from the Greeks. In the 4th century, the first Christian emperor of Rome banned the facial tattooing of slaves and prisoners. In 787, Pope Hadrian prohibited all forms of tattooing.

In the 18th century, many French sailors returning from voyages in the South Pacific had been elaborately tattooed. In 1861, French naval surgeon, Maurice Berchon, published a study on the medical complications of tattooing. After this, the Navy and Army banned tattooing within their ranks.

The ancient Celts didn't have much in the way of written record keeping, consequently, there is little evidence of their tattooing remaining. Most modern Celtic designs are taken from the Irish Illuminated Manuscripts, of the 6th and 7th centuries. This is a much later time period than the height of Celtic tattooing. Designs from ancient stone and metal work are more likely to be from the same time period as Celtic tattooing.

In England, tattooing flourished in the 19th century and became something of a tradition in the British Navy. In 1862, the Prince of Wales received his first tattoo - a Jerusalem cross - after visiting the Holy Land. In 1882, his sons, the Duke of Clarence and the Duke of York (later King George V) were tattooed by the Japanese master tattooist, Hori Chiyo.

In Peru, tattooed Inca mummies dating to the 11th century have been found. Inca tattooing is characterized by bold abstract patterns which resemble contemporary tribal tattoo designs.

In Mexico and Central America, 16th century Spanish accounts of Mayan tattooing reveal tattoos to be a sign of courage. When Cortez and his conquistadors arrived on the coast of Mexico in 1519 they were horrified to discover that the natives not only worshipped devils in the form of statues and idols, but had somehow managed to imprint indelible images of these idols on their skin. The Spaniards, who had never heard of tattooing, recognized it at once as the work of Satan. As far as we know, only one Spaniard was ever tattooed by the Mayas. His name was Gonzalo Guerrero, and he is mentioned in several early histories of Mexico.

In North America, early Jesuit accounts testify to the widespread practice of tattooing among Native Americans. Among the Chickasaw, outstanding warriors were recognized by their tattoos. Among the Ontario Iroquoians, elaborate tattoos reflected high status.

When Europeans first arived in the New World, they found Native Americans had a rich and ancient tattooing tradition. Capt. John Smith, of Virginia, mentioned Native American tattoos in his writing in the 1600's. Most tribes celebrated adulthood with tattoo puberty rites. Simple lines and geometric patterns were used and women often had lines extending from the lower lip onto the chin. Arapaho men tattooed three dots on their own chest, to prove their manhood. The Sioux among other tribes, believed that tattoos were necessary as a rite de passage into the spirit world. As a ghost warrior rode towards the "Many Lodges", he would encounter an old woman, who would demand to see his tattoos. If he had none to show, he and his horse were pushed off the path, and fell to earth, where they became aimlessly wandering spirits, who were eternally unsatisified. With the coming of Christianity, Native American tattooing disappeared and stories changed, until we only hear of the body painting of the American Indians.

In north-west America, women's chins were tattooed to indicate marital status and group identity.

Tattooing is probably the most popular form of body adornment in America today. The designs can be small and discreet or large and obvious. Many people prefer discreet designs that can be concealed for certain occasions.

Blacklight Tattoos (Image Gallery) - August 16, 2006

Jewish Positions

Orthodox Jews, in strict application of Halakha (Jewish Law), believe Leviticus 19:28 prohibits getting tattoos: Do not make gashes in your skin for the dead. Do not make any marks on your skin. I am God. One reading of Leviticus is to apply it only to the specific ancient practice of rubbing the ashes of the dead into wounds; but modern tattooing is included in other religious interpretations. Orthodox/Traditional Jews also point to Shulhan Arukh, Yoreh De'ah 180:1, that elucidates the biblical passage above as a prohibition against markings beyond the ancient practice, including tattoos. Maimonides concluded that regardless of intent, the act of tattooing is prohibited (Mishneh Torah, Laws of Idolatry 12:11).

Conservative Jews point to the next verse of the Shulhan Arukh (Yoreh De'ah 180:2), "If it [the tattoo] was done in the flesh of another, the one to whom it was done is blameless" this is used by they to say that tattooing yourself is different from obtaining a tattoo, and that the latter may be acceptable. Orthodox Jews disagree, but forced tatooing (like forced conversion) - as was the case during the Holocaust - is not considered a violation of Jewish Law. In another vein, cutting into the skin to perform surgery and temporary tattooing used for surgical purposes (eg: to mark the lines of an incision) are permitted in the Shulhan Arukh 180:3.

In most sectors of the religious Jewish community, having a tattoo does not prohibit participation, and one may be buried in a Jewish cemetery and participate fully in all synagogue ritual. In stricter sectors of the community, however, a community may have a psak (ruling or responsa with the weight of Halakha) that may forbid one's burial in a cemetary that comes under that ruling. Many of these communities, most notably the Modern Orthodox, accept laser removal of the tattoo as teshuvah (repentence), even when it is removed post-mortem.

Christian Positions

Some Christians believe that Leviticus 19:28 also applies to them, while others who disapprove of tattoos as a social phenomenon may rely on other scriptural arguments to make their point. Christians who believe that the religious doctrines of the Old Testament are superseded by the New Testament may still find explicit or implicit directives against tattooing in Christian scripture, in ecclesiastical law, or in church-originated social policy.The anti-tattooing position is not universal, however. The Christian Copts used tattoos as protective amulets.

Muslim Perspective

Following the Sharia (or Islamic Law), the majority of Muslims hold that tattooing is religiously forbidden (along with most other forms of 'permanent' physical modification). This view arises from Qur'anic verses and explicit references in the Prophetic Hadith which denounce those who attempt to change the creation of Allah, in what is seen as excessive attempts to beautify that which was already perfected. The human being is seen as having been ennobled by Allah, the human form viewed as created beautiful, such that the act of tattooing would be a form of self-mutilation. Some Muslims believe that though tattooing is not haraam (prohibited), it is nonetheless makruh (disdained). Muslims who received tattoos prior to conversion to Islam, however, face no special obstacle to religious observance. Henna patterns, however, are used among Muslim women, as distinguished from permanent tattooing.

-

A tattoo is a mark made by inserting pigment into the skin: in technical terms, tattooing is micro-pigment implantation. Tattoos may be made on human or animal skin. Tattoos on humans are a type of body modification, while tattoos on animals are most often used for identification. Tattooing has been a nearly ubiquitous human practice. The Ainu, the indigenous people of Japan, wore facial tattoos. Tattooing was widespread among Polynesian peoples, and in the Philippines, Borneo, Africa, North America, South America, Mesoamerica, Europe, Japan, Cambodia and China. Despite some taboos surrounding tattooing, the art continues to be popular all over the world.

Goddess Energies and Spiritual Photos

Tribal Tattoos Through History